1960s

1967 – Passage of Washington Clean Air Act

The Washington State legislature adopted Washington’s Clean Air Act (70.94 RCW) in 1967. This Act is the basis for state and local air pollution rules in Washington. Regulations at the state level must be as protective or more protective of human health and the environment than those of the U.S. Clean Air Act. Seven local clean air agencies enforce air pollution rules in Washington, including the Olympic Region Clean Air Agency.

1968 – Founding of Olympic Air Pollution Control Authority ( renamed ORCAA in 2003)

- One of seven local agencies

1969 – Passage of ORCAA (OAPCA) Regulation 1

1970s

1970 – Passage of Federal Clean Air Act

- The Clean Air Act (CAA) of 1970 gave the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority to regulate air pollutants. The EPA then listed and regulated six “criteria pollutants”: carbon monoxide, particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen oxides (NOx, also a precursor of smog), lead, and sulfur dioxide (a component of acid rain).

1971 – ORCAA Revises Regulation 1 to PROHIBIT TRASH BURNING BY RESIDENTS

1980s

1986 – Thurston County Designated NON-ATTAINMENT for PM10 pollution

1987 – Amendment filed addressing wood stove certification; public education; and funding for wood stove programs.

1990s

1992 – Washington State Comprehensive Plan Adopted creating Urban Growth Areas and new restrictions on burning.

Outdoor burning restricted in Thurston to help bring county back into compliance with federal air pollution guidelines.

2000s

2000 – Outdoor burning banned in high density cities and in cities with populations greater than 10,000 (includes Aberdeen, part of Hoquiam, and Port Angeles)

2000 – WAC 173-425 bans the use of burn barrels. This regulation also prohibits burning during periods of impaired air quality and prohibits outdoor burning from becoming a nuisance to surrounding neighbors and businesses.

2007 – Outdoor Burning in ALL urban growth areas (UGAs) within Washington Prohibited

2010s

2014 – All ORCAA forms digitized and made available online.

2018 – 50th Anniversary of ORCAA celebrated

More than 55 years of working for our communities

More than a half century ago, a small local government agency emerged to protect air quality in the counties of the Olympic Peninsula. The passage of the Washington State Clean Air Act in 1967 set the stage for six counties — Clallam, Grays Harbor, Jefferson, Mason, Pacific, and Thurston — to join together to form the Olympic Air Pollution Control Authority (OAPCA), later renamed Olympic Region Clean Air Agency (ORCAA).

The agency, formally launched March 24, 1968, opened with an inaugural annual budget of just $26,145 ($23,845 in federal grants — and this prior to passage of the federal Clean Air Act — and $2,300 in state grants). The first several months of the agency’s existence were spent developing formal local air quality rules and regulations. Those policies were adopted by the agency’s board of directors in 1969 as OAPCA’s Regulation 1, which were in effect the local counterpart of the state clean air act.

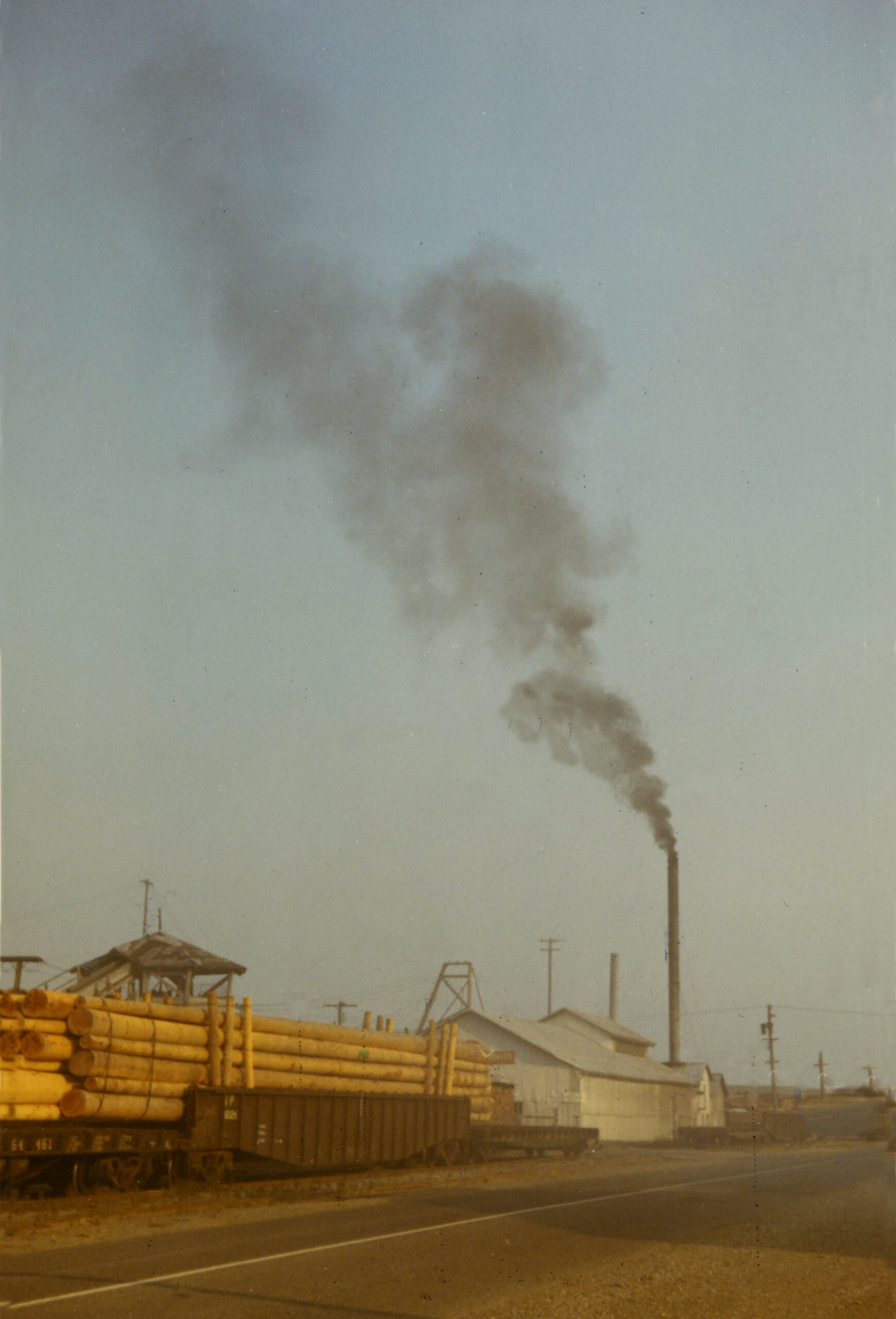

During those initial years of operation, the primary focus of the agency was large industrial sources, such as the Farwest Aluminum Corporation of Aberdeen and wood products companies around the region. Through the first two years of work, the agency staff also tackled the issue of sawmill wood-waste burners, known colloquially as ‘wigwam burners.’ Those large cone-shaped metal structures, topped with mesh panels, were considered by the industry to be the ultimate, ‘clean, efficient waste burners.’ Those forms of burners were finally banned by state law in 2005!

The creation of the state Clean Air Act (Chapter 70.94 RCW, later recodified as 70A.15 RCW) in 1967 clearly defined Washington’s rationale for air quality protections, and outlined the need for regional agencies such as ORCAA.

The opening statement reads, in part: “It is hereby declared to be the public policy of Washington Clean Air Act the state to secure and maintain such levels of air quality as will protect human health and safety, policy, and – to the greatest degree practicable – prevent injury to plant and animal life and property, foster the comfort and convenience of its inhabitants, promote the economic and social development of the state and facilitate the enjoyment of the natural attractions of the state.

“The problems and effects of air pollution are frequently regional and interjurisdictional in nature and are dependent upon the existence of urbanization and industrialization in areas having common topography and recurring weather conditions conducive to the buildup of air contaminants. It is also declared as public policy that regional air pollution control programs are to be encouraged and supported to the extent practicable as essential instruments for the securing and maintenance of appropriate levels of air quality.”

One of the first tasks of the board of directors of the new agency was hiring staff. During the November 1, 1968, meeting of the Board of Directors – composed of representatives from the cities and counties comprising OAPCA – they agreed to hire the agency’s first employee. On December 10, 1968, Joel Durnin became the first agency employee: Control Officer (title to be changed many years later to Executive Director) for $13,000 per year.

Mr. Durnin and the Board of Directors next addressed the problem of eliminating the toxic smoke produced during trash burning at municipal garbage dumps. Most cities and counties operated at least one large communal ‘dump’ where residential and business waste was piled and burned on a regular basis. A letter, dated Feb. 27, 1970, from the City of South Bend to the OAPCA Control Officer Durnin underlined the challenges faced by the agency, and the municipalities it served. That letter stated, “We request the City of South Bend be allowed to burn garbage until a land fill becomes available. South Bend has collaborated with Pacific County on a land fill garbage dump. The Director of Public Works…has indicated the land fill is in the planning stages.”

Other counties and cities also asked for temporary variances while working out the logistics of building new landfills – facilities that required permits and zoning changes from other government agencies. In short, the work to protect the air was slowed by other laws designed to protect land and water. But by the early 1970s most of those trash burning ‘dumps’ were closed, and large landfills were in use.

Unfortunately, though the scale is much smaller today, the challenge of residential trash burning continues. ORCAA staff regularly respond to smoke complaints resulting from illegal trash burning by individuals. Trash burning, and the use of burn containers such as burn barrels, is illegal under the state Clean Air Act, as well as ORCAA’s own regulations.

An even bigger task facing the OAPCA in its early years, though, was curbing industrial emissions. With a broad assortment of wood-products mills throughout the six-county region, industrial air pollution topped the list of issues to be addressed. Cedar shake/shingle mills burned their waste wood in those ‘wigwam’ burners. Plywood and lumber mills burned ‘hog fuel’ (i.e. wood waste) to power their boilers. But according to ORCAA’s longest-serving Control Officer (now known as the Executive Director), “pulp mills were the big problem for us.”

Chuck Peace, OAPCA Control Officer from 1976 to 2004, said “Those pulp mills put out a lot of smoke and toxic emissions, and their solution to compliance at the time was simply to build their (smoke) stakes a little higher.” Compliance was difficult in part, Peace said, because, “when we found violations of the law, the agency wasn’t able to give a ticket that carried a big enough value for the industry to take notice of.” With maximum fines capped at just $1,000 for much of the first two decades of its existence, “we were trying to achieve compliance with too small of a stick.” Eventually, the maximum penalty was increased. Today, the maximum fine ORCAA can assess for each violation is capped at $14,915.

Another problem ORCAA faced, especially in the early 1980s, was the prevalence of illegal drug manufacturing in remote areas of its jurisdiction. The problem, in terms of air quality, came after police raided those ramshackle old building used by the groups ‘cooking’ methamphetamine. Once the illegal operations were shut down, Peace said, “the county sheriff departments usually wanted to burn those structures down. Proper demolition was just not safe, or practical, given the hazards of poisons and even explosives that could be found,” Peace said. “So, we were asked for, and gave, multiple waivers for demolition burns of drug houses.”

Issues such as that highlight the importance of having local agencies such as ORCAA, said Peace. He noted that even after 24 years leading the agency, he recognized the need to continue to evolve and build on past successes. “I think Washington (state) is doing things right. In fact, Washington’s program is awesome compared to what I see in other parts of the country.”

Peace retired to property he had long owned in the Missouri Ozarks. “Here in Missouri, opening burning is pretty much unregulated and the air can get pretty nasty at times. I think Washington’s program is awesome. That three-tiered process on air pollution control – using local agencies to enforce local, state, and federal clean air regulations – is really the best way to go. That’s what the most effective states are doing: Partnering states with local agencies, supported by federal participation, to work directly with people.”

Richard Stedman succeeded Peace, taking over the role of Executive Director in 2004. One of Stedman’s first tasks was securing a long-term home of the agency. He found a building in West Olympia and arranged to finance the purchase through Thurston County. He also undertook the effort to rebrand the agency – other local air agencies were also taking on this task. The Olympic Air Pollution Control Agency (OAPCA) became the Olympic Region Clean Air Agency (ORCAA) and a new logo was adopted to go with the new name.

Stedman resigned from ORCAA in 2008 to take on the challenge of leading California’s Monterey Bay Air Resources District. The ORCAA Board conducted a national search for a new Executive Director and found their new agency leader in their own backyard. Francea (Fran) McNair had served as Deputy Director of the Washington Department of Natural Resources for 8 years, following a career in local government leadership. Among other vital projects, McNair guided ORCAA through the housing crisis recession and reorganized the agency’s building to maximize rental income from the portions of the building not needed by ORCAA.

McNair retired early in 2022, and following another national search, the ORCAA Board found its new leader at the Washington Department of Ecology (ECY). Jeff Johnston, Ph.D., took over the ORCAA Executive Directorship in February 2022, and quickly helped set the agency step up to the challenges of a post-COVID world. Johnston guided the agency into a process of rebuilding the agency website, launched another minor agency rebranding with an updated logo and messaging, revised outdated agency burning regulations, and developed a new approach to address illegal burning in homeless camps. Johnston crafted partnerships with local jurisdictions and non-profit homeless advocacy groups to provide additional resources for dealing with trash burning in homeless encampments in Thurston County.

More than fifty years after its creation, ORCAA still faces challenges. Some are similar to those faces by the agency in 1960s, but many are very different, though no less important. Around 800 industrial sources are registered with ORCA. And smoke from wood burning remains as one of the largest sources of air pollution in our region. Today, that smoke comes from use of wood stoves and fireplaces for home heating, outdoor burning of residential yard waste, or large-scale open burning from land clearing and silvicultural activities. ORCAA works closely with other agencies on various outdoor burning issues, and the agency strives to reduce wood smoke emissions from home-heating devices by encouraging clean burning practices. ORCAA also partners with the state Department of Ecology to address the areas most impacted by wood smoke by to providing financial incentives to homeowners to replace their old, uncertified woodstoves with clean home-heating appliances such as ductless heat pumps or natural gas stoves.

Facing the realities of a world impacted by climate change, ORCAA also finds itself with new challenges such as dealing with wildfire smoke – sometimes transported from thousands of miles away. In ORCAA’s jurisdiction, the worst air quality days in recent years have all been due to wildfire smoke from distant sources. To address these problematic events, ORCAA mains strong relationship with local and state health departments, other air agencies, and local, state, and federal fire agencies to provide the public with information and resources to help them cope with the smoke.